|

The

following observations represent my opinions. While I believe that the opinions expressed here are consistent with c.

212 § 3, I submit all to the ultimate judgment of the Catholic Church.

The letter “c.” stands for “canon” of the 1983 Code of Canon Law. All

translations are mine, even if they coincide at times with those of others. Dr. Edward N. Peters

Note: If you have

subscribed to Canon Law Blog but do not receive timely notices of

updates, we might have a bad email address for you. With each notice,

a few emails are returned to us, and we have, of course, no way of

letting those subscribers know there is problem.

|

|

In the Light of the Law:

a

canon lawyer's

blog on current issues

Blog

Archives 2002

|

|

The

Baltimore Verdict

|

17

December 2002 |

|

To

no one’s great surprise, the man who admitted shooting a priest three

times in broad daylight was found Not Guilty by a Baltimore jury that

believed he was, at the time of what prosecutors argued was plainly attempted murder, suffering from a

“dissociative disorder”, itself the result of the man's being (and

no one

seriously doubts this) sexually abused by the priest a decade ago. My

criticism is not so much of the verdict (however much it reinforces the

quip that the innocent want a trial by judge while the guilty go for a jury)

for clearly, the trauma of childhood sexual abuse can result in a legion

of psychological and emotional disorders perduring for years. The

greater problems, as I see it, are the reactions to that verdict.

First,

the exonerated shooter is quoted as saying that he hopes the verdict

will send a message of hope to other victims of clergy sexual abuse.

Well, if I may ask, just what message of hope could that be? That

they too might suffer from dissociative disorders and might as a result

find themselves shooting priests in the street? Presumably, that is all

the verdict said about the man’s actions in this case, and that

does not sound very “hopeful” to me. If the man sees more

than that in the verdict, it makes one wonder just how sincerely his

insanity defense was offered in the first place.

|

|

Pope

Paul VI

Si

vis pacem,

cole iustitiam.

|

Second,

Baltimore’s William Cardinal Keeler, (who, in full view of the jury,

stopped to shake hands and exchange cordialities with the priest's assailant on his way to the witness stand)

says he hopes that the verdict

brings a measure of peace to the community. But didn’t Pope Paul VI

teach us that peace is the fruit of justice? If so, the highly dubious

quality of the scant justice wrought in this case leaves little basis for

the Cardinal’s hopes.

For

decades, many Catholic priests inflicted grave injustices on children, and

many Catholic bishops responded, if at all, wholly inadequately to those

crimes. During most of that time, civil authorities looked the other way,

too. In other words, the two greatest social institutions, the Church and

the State, grievously withheld basic justice from young victims. We should

not be surprised, then, that we, like other societies abandoning the rule

of law, now see, quite literally, violent consequences in our streets.

Nevertheless,

those who tell us that the Baltimore

verdict is the dawn of hope for victims and a harbinger of peace for the

community are false prophets. Instead, I suggest the Baltimore verdict is a tragic

endorsement of a savage response to a despicable crime.+++

|

|

|

Friendly

Fire

|

15

December 2002 |

|

According

to a Dec 15 article

by Marion Lloyd in the Boston Globe:

|

|

Sometimes

people on the same side of an issue say things that they think

are helpful to their friends, but in reality this "friendly

fire" might harm the efforts of their allies. I believe

this might have happened in the present case.

|

|

Catholic

officials [in Mexico] voiced sympathy for [Bernard Cardinal Law]

the disgraced Boston prelate. ''This should not be taken as an

admission of guilt,'' Bishop Abelardo Alvarado Alcantara,

secretary general of the Conference of Mexican Bishops, said

Friday. ''Due to the enormous pressure from dissident groups,

including priests, he generously decided to do what he felt was

his duty ... in the best interest of his diocese.''

|

A

resignation is not an admission of guilt per se, but neither is

it a ringing reiteration of one's defense. Cardinal

Law's resignation should have been firmly presented and accepted

months ago because it was fundamentally the right thing to do.

Instead, the delay gave some dissident voices the

opportunity to pile on the beleaguered prelate (whom they

opposed for, shall we say, less noble reasons) and left the

impression that his announcement was a capitulation to pressure,

instead of an action justified in itself.

|

|

Alcantara

said he thought Law had been unfairly judged for his past

actions by the stricter standards of responsibility that have

emerged as the result of the priest sex scandal.

|

I

must question the implication that canonical norms against

clerical sexual misconduct have significantly changed here or

that the obligation of bishops to protect their flocks from

clerical sexual predators is something new in canon law. But

the point is, however, irrelevant because what "brought down"

the Cardinal are not actions from decades ago, but decisions

made by him in just the last few years.

|

|

''It's

as if we wanted to judge crimes today that at the time weren't

considered serious,'' Alcantara said. ''The bishop can't be

expected to denounce a priest and hand him over to a civil

judge. It's like when a father knows his son is guilty, he tries

to protect him and help him correct the mistake. It's a

different mentality.''

|

I

repeat, clerical sexual abuse of minors has always been grave

violation of ecclesiastical discipline, and bishops have always

known it. As for the analogy that suggests fathers ought

to hide their criminal sons from the law,

well, maybe it is a different mentality after all, but

certainly it's one that loving fathers may responsibly reject.+++

|

|

|

The Manchester

Agreement

|

11 December

2002 |

|

WASHINGTON

(December 10, 2002) -- Belleville Bishop Wilton D. Gregory,

President of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops,

issued the following Statement concerning the

Agreement

announced today between the Diocese of Manchester and the Office

of the Attorney General of the State of New Hampshire:

|

|

One

cannot but feel sympathy for Bishop Wilton Gregory,

President of USCCB, upon whose watch four decades of clerical

sexual misconduct have come home to roost. I realize that in his

position, he (no more than anyone else would have been), is not

entirely his own man, and I have on several occasions praised his

earlier statements on this burgeoning crisis. But now, after

reading the statement issued under his name on the Manchester

agreement, I feel it is time for some criticism.

|

|

The

Diocese of Manchester has reached a legally binding mutual

agreement with the office of the Attorney General of New

Hampshire which involves acknowledgment by the Diocese that the

State has evidence likely to sustain a criminal conviction

against the Diocese for a failure in its duty to care for young

people.

|

The

enormity of the admission in Paragraph 1 (a Catholic

diocese admitted engaging in criminal conduct) calls for, before

anything else, an immediate

and profound expression of renewed sorrow. There is none. |

|

I

understand the pressures under which the Diocese acted, and I

note that this resolution is specific to the facts in the

Diocese of Manchester and to the laws of the State of New

Hampshire. It does not in any way indicate agreement on the part

of any other diocese or of the United States Conference of

Catholic Bishops in the legal analysis on which the Office of

the Attorney General of New Hampshire has acted.

|

Is

Bp. Gregory suggesting that the “pressure under which the

Diocese acted” should temper our reading of its admission?

Does the Diocese admit to criminal activity, or not? If so, was

its admission free, or not? If it was free, what matters whether

pressures deriving from diocesan criminal misconduct were

present? And why protest that the Manchester agreement in no way

reflects the opinions of other dioceses or the USCCB? What

question is being raised here?

|

|

However,

there are elements in the agreement which parallel the bishops'

own decisions last June which are embodied in the "Charter

for the Protection of Children and Young People."

|

This

statement actually means so little, that it cannot be commented

upon. |

|

In

particular, the idea that an audit function would be helpful in

resolving this terrible problem permanently was adopted with the

creation of the Office of Child and Youth Protection. With its

director, Kathleen McChesney, in place, every diocese will now

benefit by an audit of their efforts to keep children safe.

|

Phrases

like “audit function” reinforce the pervasively bureaucratic

appearance of the bishops’ response to what is fundamentally,

at every level, a moral crisis. The cold phrase “audit

function” rings in most ears as dealing with financial

concerns. It is incumbent on authors to explain their

idiosyncratic usage of terms common from other fields.

|

| We

did this because, as bishops individually and collectively have

acknowledged, there were mistakes and failures in our handling

of cases of abuse of minors by clergy. |

Bp.

Gregory speaks of “mistakes

and failings.” Just “mistakes and failings”? How about “sins”,

or even “crimes”? Isn’t that what the

Manchester agreement concedes? One doesn’t face

prosecution for “mistakes”, one faces it for crimes.

Avoidance of that stark term fools no one. Of course, if the

Diocese does not feel it engaged in criminal activity, it should

say so. But if the Diocese concludes that its activities were

criminal, others have little basis to doubt that admission.

|

| They

were serious ones, but they are not attributable to

intentionally bad acts but, most often, to a lack of awareness

of the extent to which this behavior entails a deep sickness

which is resistant to treatment. |

Does

Bp. Gregory think the only crimes for which one should be

prosecuted are “intentional” crimes? No one I know is

suggesting that bishops routinely assigned sexual miscreants

with the intention that they would abuse minors, rather, the

claim is that some bishops were criminally negligent in

their toleration of these men in church work. As for whether the

misconduct was a result of a “deep sickness”, well, I think

we can agree, some were. But were all of them so? What

do we think about those cases? By the way, could not this same

“deep sickness” defense be used to defend, say, a drunk

driver who goes out and kills people, albeit unintentionally? I

ask, so

what?

|

| The

errors of specific persons, at specific times and places which

may have endangered children, cannot be attributed to the

"Church" as a whole without overlooking the lives of integrity

and good works of ministers of the Church in our country

throughout its history. |

"May"

have endangered children? May? This paragraph plainly

tries to paint a very narrow picture (“specific persons, at

specific times and places”) of a very

broad, even systemic, problem. It’s yet another attempt at

bureaucratic minimalization. No one honestly doubts but that

thousands of fine Catholic priests have been at work over the

last 40 years. That does not excuse the episcopal

toleration of hundreds of sexual offenders in clerical

ranks for decades. To try to avoid saying that, and saying it

plainly, is but to fan the flames of cover-up suspicion already

raging out of control. It certainly does not ring as true as did

Bp. Gregory’s fine statements this past summer.

|

| There

is a difference between mistakes and intentional wrong

doing. |

Never

talk down to readers. This crisis is not about mere

"mistakes". And we are not talking (at least in regard

to most bishops, a distinction Bp. Gregory himself admits

later) about intentional episcopal wrong-doing. We are talking

about the huge middle possibility of culpably negligent

episcopal behavior. That is what people want to hear bishops, where

appropriate, admit to frankly and without bureaucratic

dissimulation or word-mincing.

|

|

As

Church leaders, we are willing to own up to our mistakes.

However, except for those very few who personally have also been

perpetrators, church leaders have not intentionally endangered

the welfare of children.

|

M.O.S. |

| We

will always repent of the mistakes that resulted in abusers

being kept on in ministry to hurt and abuse more children. We

give our full support to means, such the Office of Child and

Youth Protection, which will help us prevent abuse in the

future. |

One

does not “repent” of “mistakes”. One learns from them.

One repents from sins. Bishops should be

unequivocally holding themselves to that standard, and they

should be calling the rest of us to repent of ours. Also, among

the welcomed “means” for preventing child abuse in the

future, does Bp. Gregory include agreements like Machester's, or

not? I hadn’t thought it was a question till I read this

statement. Now, I’m not sure.+++

|

|

|

|

Standard

Cardinal Coat of Arms

|

Cardinal

archbishops, like all ecclesiastical office holders, may resign their sees

for any just cause (c. 187). The reasons that suggest the appropriateness

of a pastor resigning his parish (cc. 1740-1741) would, mutatis

mutandis, be relevant to the case of an archbishop considering

resigning his see.

If a cardinal resigns his pastoral or curial office (indeed

all are requested to do at age 75 anyway, cc. 354 & 401) he does not

thereby lose the power of voting in a papal conclave.

That, he retains until age 80, at which point his right to vote

automatically lapses.

There is no mechanism for forcing a given cardinal to attend

a papal conclave, however, and Church law expressly allows a

conclave to proceed despite the absence of one or more cardinal

electors, though in such circumstances, it is expected that a

cardinal who declines to attend, presumably for grave reasons,

will so inform the conclave. |

|

|

|

On Dec.

3, 2002, Joseph Cardinal Ratzinger made the following comments

at a conference in Spain: “In the Church, priests also are

sinners. But I am personally convinced that the constant

presence in the press of the sins of Catholic priests,

especially in the United States, is a planned campaign, as the

percentage of these offenses among priests is not higher than in

other categories, and perhaps it is even lower. In

the United States, there is constant news on this topic, but

less than 1% of priests are guilty of acts of this type. The

constant presence of these news items does not correspond to the

objectivity of the information nor to the statistical

objectivity of the facts. Therefore, one comes to the conclusion

that it is intentional, manipulated, that there is a desire to

discredit the Church. It is a logical and well-founded

conclusion.” Source: Zenit

ZE02120324. |

"Maria

Monk" |

I

agree with the Cardinal. I would simply add, though, as one who has

watched, and tried to fight, anti-Catholicism in the US media throughout

my adult life, that even the most outrageous accusations of the infamous

Maria Monk canard pale against the real life deeds of scores, if not

hundreds, of our priests, frequently with the knowledge of, or at least

the culpably negligent ignorance by, our bishops. Anti-Catholics in the US

media have no need for lies when the truth condemns. Yes, our enemies

rejoice over us. But it is we who have betrayed the City into

their hands. God surely sees the hearts of those who hate the Church and

delight in its suffering. But, in the meantime, each of us has contributed

to this debacle by our own sins, and, just as surely, we must each

contribute to the Church’s recovery by our own acts of personal

repentance. +++

|

|

|

Zenon

Cardinal Grocholewski, one of the Vatican's most respected canon

lawyers,

directs the Congregation for Education.

|

The

Congregation for Education, the Vatican dicastery that accredits pontifical

faculties around the world, announced November 19 in its decree Novo

Codice, that it will henceforth require a

third year of full-time canonical studies for the degree of licentiate in canon law

(J.C.L.). The Congregation also

reiterated its expectation that all canonists, notwithstanding the wide

availability of basically reliable canonical translations, still be able to read

Latin, the official language of canon law. Moreover, the practice of

waiving First-Cycle theology requirements for civil lawyers (a practice I am

pleased to note was not adopted by my alma mater) has not only been

prohibited, but an additional year of theological study will now be required of all

incoming JCL students not already possessing a Masters in theology. All of these changes are

steps in the right direction. They are, I suggest, more evidence that canon law

continues its re-emergence from the cloud of antinomianism under which it has

labored since the Second Vatican Council.

|

Considering

only, for example, how much of the recent clergy scandals in the USA can be

traced to ignorance of, or disregard for, canonical directives in Church life,

it's good to see Rome taking positive steps to augment the expertise of those

who will be increasingly called upon to advise bishops and others on the

juridical aspects of ecclesiastical ministries and apostolates. But these are

only steps and more remains to be done to increase the vital professionalism of

modern canon law. I’ll be addressing those points in due course.+++

The

revised norms for handling allegations of clerical sexual misconduct are out,

and while, strictly speaking, they still require approval from the USCCB and,

once more even, from Rome itself, there is little doubt but that both

ratifications will be secured promptly. Predictably,

some are presenting the revised norms as virtual

endorsements of the USCCB’s summer proposals, while some, conceivably, would

like to cast the new norms as a trouncing of the bishops efforts. As usual,

neither extreme interpretation is accurate.

As I

had hoped, the bishops’ excellent Preamble remained virtually intact.

Deftly, however, Rome chose the Preamble to insert a badly needed

clarification as to what legally constituted the sexual abuse of minors (i.e.,

“an external, objectively grave violation of the Sixth Commandment”), thus

remedying one the weakest parts of the bishops’ summer efforts.

The

bishops’ call for all dioceses to file policies on sexual misconduct with the

USCCB has been retained, but the revised norms now explicitly demand that such

policies honor the requirements of procedural canon law (e.g., Canons

1717-1719).

The

bishops’ plans to have outside boards conduct the canonically mandated

investigations of clergy sexual abuse allegations has been rejected by Rome;

such boards now merely advise bishops on what was, all along, their

responsibility. Rome has also insisted that all the members of this board be

Catholic (pace the USCCB’s press release on this point) albeit persons

financially independent of the Church. In both respects these are major

improvements over the original proposals.

The

so-called “appellate review boards” are completely gone, saving the Church

and the people she serves the confusion of a whole parallel system of

institutions for dealing with just one kind of case. And the earlier skimpy

outline of investigation procedures has been considerably beefed up by express

references to various relevant canons that, all along, have been in force,

waiting to be applied. Importantly, Rome has reiterated the rights of the

accused not to be subjected to involuntary psychological investigation, I hope

once and for all.

Both

versions of the norms recognize that for even a single act of child sexual abuse

an offending cleric will be removed permanently from ministry. Amen to that,

especially now that the working definition of child sexual abuse is much less

subjective than was earlier envisioned.

Two

new and important provisions inserted by Rome remind bishops that 1) they

already have what canonists call “executive power of governance” enabling

them to deal promptly with potential abuse situations not immediately addressed

by criminal canon law, and 2) that bishops can request from Rome, even without

the cooperation or consent of the cleric in question, what is termed an ex

officio dismissal from the clerical state for offensive behavior. It is, I

suggest, another quiet affirmation that canon law was not lacking as this crisis

mounted, it more often was simply not being applied.

We can

leave to others the interesting, if largely irrelevant, question as to the

degree to which the revised norms should be seen as endorsing the bishops’

original proposals from this summer. One’s time is better spent, I suggest, in

identifying any possible remaining weaknesses in the policies (there are some, I

think), and then getting about the task of protecting children from sexual

predators among the clergy. +++

|

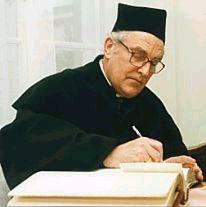

Francis

Cdl. George

Chicago,

IL

|

Abp.

William Levada

San

Francisco, CA

|

Bp.

Thomas Doran

Rockford,

IL

|

Bp.

William Lori

Bridgeport,

CN

|

The four

American prelates who worked with Roman officials to obtain a significantly

improved

procedure for dealing with the crisis of clergy sexual misconduct with children.

|

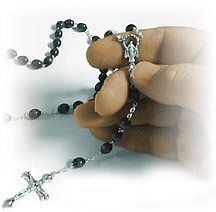

The

authority of the Roman Pontiff to establish new mysteries in the Marian

Rosary is certain (c. 331). As a result of Pope John Paul II issuing his

apostolic letter Rosarium

Virginis Mariae,

the canonical directive to pray the rosary given to seminarians in Canon

246 § 3 and to those living the consecrated life in Canon 663 § 4 will

now be observed by praying a rosary consisting of fours set of

mysteries, instead of the traditional three.

For

the rest of us, likewise, when we pray the rosary as an authentic

devotion (see cc. 214, 839, & 1186) we will do so in light on the

pope’s call to expand our meditation as outlined in Rosarium.

|

|

There is, of course, no canonical obligation on us to pray the rosary at

all, and for those who do so, the days suggested for praying specific

mysteries are, strictly speaking, just that, suggestions. Other manners

of praying (e.g., a decade a day, chosen in a way consistent with the

liturgical season) are acceptable. Finally, the revised format of the

Rosary is unquestionably eligible for indulgenced prayer in accord with Handbook

of Indulgences, Other Grants, No. 48. Sancta Maria, Mater Dei,

ora pro nobis peccatoribus! +++

|

The Vatican is about to reject, at

least in substantial part, the USCCB’s novel proposals for dealing with the

clerical sexual abuse of minors crisis. This is good news.

Except for its Preamble (which reads quite well, I think), almost the

whole of the rest of the June 14th document was problematic. It failed

to define terms, it ignored whole stretches of canonical criminal

procedure, and, though billed as the charter for episcopal

responsibility, it actually removed from bishops considerable authority

for responding to these cases (on the Church’s behalf, no less) and

delivered it to quasi-independent committees, themselves only vaguely

configured.

|

Pope

John Paul II

Man

of Prayer, Man of Law |

Chiefly, though, the Charter never recognized that the canons already on

the books of the 1983 Code of Canon Law will, if applied responsibly, go

a long, long way toward punishing wrong-doers, aiding victims, and

preventing future abuse from occurring. The problem has not been the

law. The problem all along, I suggest, has been too many bishops’

failure to apply canon law diligently. I see in the Vatican’s

rejection of this proposed charter a clear directive to apply the canons

now in force, and to the degree they might need reforming (canon law,

like the Church, always needs some reforming), Rome will, as it has in

the past, consider reasonable proposals.

Pope John Paul II is starting his 25th year in the Chair of Peter with a

bang: a beautiful document updating the laity’s chief Marian devotion

on one hand, and a firm reassertion of the measured application of

disciplinary law on the other. Pro papa nostro, agimus Tibi gratias,

Domine! +++ |

Update:

(18 October): "When it comes to beating the Catholic Church", said G.

K. Chesterton, "any stick will do." It's already started:

Hostile critics are charging the Vatican with everything from stupid

curial blindness, to clerical wagon-circling, to an out-and-out

cover-up, based on its rejection, for the most part, of the USCCB's

proposed norms on clerical sexual misconduct. In reality, though, the

Vatican wants bishops, not vaguely described committees, to take real responsibility

for supervising Catholic clergy and allegations of misconduct; it wants

canon law to be applied fairly and vigorously against such dangers, and

will not countenance resort to ill-defined policies thrown together

under media spot lights; and it even dares to suggest that in the flood

of verified allegations of disgusting clerical misconduct, there are at

least a few innocent priests (and others) who are being railroaded by

the same disrespect for fundamental legal procedures that helped get us

into this horrible mess in the first place.

A considerable number of the men who actually created this crisis, whether

they be priests who engaged in gravely illicit behavior, bishops who did

not recognize or did not act on that information, or some advisors who

helped shape an attitude of neglect, are now gone from the scene,

leaving others behind to clean up their mess. The lack of

credibility that current committed Catholic leadership has on this topic

is the price it has to pay for other's mistakes. So be it. Time and

again the Church has experienced the pain of having wandered from its

own published principles and the solution was rarely found in the

concoction of new structures, committees, position papers, charters, and

what have you, but rather the humble return to the perennial principles

of sound moral, pastoral, and canonical wisdom.+++

Pro-Life Bishops vs.

Pro-Abortion Politicians, 4 October 2004

The US

bishops are planning a statement on the upcoming 30th anniversary of Roe v. Wade,

i.e., the infamous case legalizing abortion in America. Since Black Monday,

America's bishops have been unwavering in expressing their opposition to

abortion. But if some of them feel it's perhaps time to go beyond words (yes, I

know, some bishops have made sacrifices for life, efforts perhaps known but to

themselves and God), at least two public canonical responses seem immediately

worth considering.

|

1) Catholic politicians who

support abortionism involve themselves in objective manifest grave

sin (Evangelium vitae, 73). Such persons, to the extent

that they persist in these misdeeds, make themselves ineligible for admission to

Communion (c. 915). Diocesan bishops have the right and duty to see to the

spiritual welfare of all those in their care (c. 383), of maintaining Catholic

discipline on faith and morals (c. 392 § 1), and of preserving the Eucharist

from unworthy reception (c. 392 § 2). The application of Canon 915 does not

require a penal process, and therefore a bishop is free to shape his own

approach to individual circumstances. I already wrote an extended

canonical study of an actual case wherein a bishop applied Canon 915 against

a pro-abortion politician, so I won't repeat those matters here. The point to take

from this is that the norm is on the books, ready to be used.

2) Canon law makes it a crime for Catholics to use "…public

speeches, published writings, or other instruments of social communication to…gravely

injure good morals…" (c. 1369). I think many of the activities of

pro-abortion Catholic politicians, even in the act of casting their votes for

death, to say nothing of the variety of public affairs that politicians

typically engage in, meet exactly the requirements of this canon, which visits

upon its violators a "just penalty". While this canon is expressly a

penal canon, demanding therefore the observance of penal procedural law (e.g.,

cc. 1341-1353), the flexible, indeterminate penalty makes Canon 1369 especially

worth considering by bishops concerned to address the harm being caused by

pro-abortion Catholics in politics. Moreover, contempt for what would likely be

lesser penalties to start with can result in escalation of penalties against the

recalcitrant (cc. 1393 & 1399). This canon too I have discussed in a recent interview.

As with Canon 915, the law is already in effect. What's required is the will to

use it. +++ |

It's

a mortal sin to tell

people

that

they may kill a pre-born child.

|

|

Some

weeks ago, a small but thoughtful group of US bishops proposed convoking what

would be the "Fourth Plenary Council in America" in order to deal with

the crisis of clerical sexual misconduct. Since then the list of supporters of

the idea has slowly grown. A plenary council is, of course, a serious thing. It

has genuine legislative authority (c. 445), a power that is not widely

distributed in the Church (c. 135). An examination of the canons on plenary

councils (cc. 439-446), however, raises some questions that need to be addressed

before moving forward. In brief, the problem is not the council, it's

the conference.

Specifically, the United Stated Conference of

Catholic Bishops (the recently reorganized USCCB) would have almost complete

agenda-making and conduct-governing authority over a national plenary council (c. 441). But

this is the same conference on whose watch the clergy misconduct crisis has

festered for years. Its efforts to address priestly misconduct (and there have

been some efforts, to be sure) have not generally been such as to inspire

confidence among the faithful yet.

|

The

last Plenary Council for the United States met

in Baltimore,

Maryland, in 1884. |

One might counter that, at least in part, some

of the bishops who made up the conference in years past (when little was being

done nationally to check priestly misbehavior) have since retired, leaving

relatively more influence to recent appointees. These, there is reason to hope,

seem more willing to confront criminal behavior in the ranks of their priests.

Ah, but this raises a second concern, namely, that the conference is empowered

to invite even retired bishops to a plenary council, which in turn would be

required to give them a deliberative vote (c. 443 § 2). Such an action would

dilute the influence of exactly those newer bishops whose voices most need to be

heard.

A plenary council, if one is held, should limit

its agenda to the topic of clergy sexual misconduct and only active bishops who

have to face the crisis here and now should be invited with a deliberative vote.

Finally, the Holy See needs to communicate that it is truly ready and willing to

reject any legislation that might be inconsistent with genuine Catholic

character (c. 446). +++

Update,

November 10: The November issue of Catholic World Report,

pp. 32-33, features opinions from several prominent US Catholic observers on

the advisability of convoking a Plenary Council for America.

If all

things were equal—and they never are—but if all things were equal, I would

prefer to see people receive Holy Communion standing. I personally like the

symbolism of those who have been raised to new life in Christ receiving Him

standing, as was done in the early Church. But this “ancient practice” argument

cannot be pressed very far, at least not unless one is also willing to

go back, say, to seven-years-on-bread-and-water penances. The selectivity of

those who argue for the return of some ancient practices while avoiding, if not

vetting, others, borders on the hypocritical.

|

But I

would never dream of withholding, or of countenancing the withholding of, the Eucharist from someone because of their choice to

receive Jesus kneeling. This gesture of reverence for the real and substantial

presence of Our Lord in the Eucharist has as distinguished a pedigree in the

Church as does the erect posture. Besides, among fully-initiated Catholics (c.

842 § 1) who have observed a one-hour fast (c. 919 § 1), only “the excommunicated,

interdicted…or others who obstinately persist in manifest grave sin” are

to be denied the Eucharist (c. 915. See also cc. 213, 843 § 1, & 912). It is

inexcusable to treat devout Catholics who choose to receive Holy Communion on

their knees as if they were suddenly grave sinners.

|

|

If

nothing else,

the timing of this change is wrong. Instead of removing a traditional sign of

belief in the Eucharist at the very time when most studies show Catholic belief

in that mystery to be at modern lows, we should welcome a reasonable and popular

gesture of faith in the Blessed Sacrament. Finally, if a change in discipline does

come, it would be nice if, for a change, it were not sprung on loyal but

bewildered Catholics who have been encouraged in one practice for years, only to

be chastised for not reading the latest liturgical tea leaves quickly enough to

suit the makers of liturgical morals. The faithful deserve some pastoral

preparation. +++

|

Abp.

George Pell |

Archbishop George Pell of Sydney

Australia should not have surrendered his ecclesiastical authority for

an indeterminate period of time. His gesture of 20 August 2002 in

response to sexual misconduct accusations against him is meant to convey

his willingness to undergo the rigors of investigation and his

confidence about his own vindication. It is obviously well-intentioned.

It has the air of a “class act” undertaken by a true gentleman (not

surprising, considering that is exactly what Archbishop Pell is.)

But it

has no foundation in a canon law system that only recognizes only outright

resignation from episcopal office (c. 401) or, more rarely, a declaration that a

see has been “impeded” (c. 412) by conditions clearly not satisfied under

the present circumstances. As archbishop, moreover, Dr. Pell could not have used

his powers to interfere with various investigations that were being conducted

independently of his office in the first place. His action therefore, already extra

legem (outside the law, but not exactly contrary to it), accomplishes little

concrete in the order of procedures. |

What

it does do, I am afraid, is to establish a dangerous precedent or “unwritten

expectation” for others. If a man as upright and as innocent as (I believe)

Archbishop Pell is will surrender high ecclesiastical office for an extended

period of time on the flimsiest of accusations, what is to prevent every bishop,

not to mention clerics or lay workers, from being held to that same unreasonable

standard, especially given that few accusations are likely to be as obviously

worthless as are those under which Archbishop Pell labors. Will not such

expectations of “temporary resignations” now be demanded by every enemy of

the Church who wants to gum up its administrative and pastoral life? Moreover,

should Archbishop Pell now order, or even allow, one of his own faithful pastors

or lay workers to drop his duties to Christ and His people in response to

accusations that the archbishop himself might be certain are false? If so, at

what point exactly does an investigation into these sorts of accusations end?

This is far from clear, leaving the terminus of such an anomalous situation

helplessly up in the air. If nothing else, these are some of the questions that

need to be addressed before concluding in favor of the archbishop’s action.

+++

Update

1:

It is now October 8th, and the archbishop’s “accuser” is

apparently still refusing to cooperate with a civil investigation of his

allegations, all the while leaving Dr. Pell in a foggy accusational limbo. Let

the investigations continue, but meanwhile the esteemed archbishop should

declare his self-imposed exile over, and resume his praiseworthy leadership of

the Church of Sydney. +++

Update

2:

As of the 15th of October, an independent inquiry being unable to substantiate

any of the accusations made against Abp. Pell, he has resumed his duties. Deo

gratias. +++

Prof.

Rev. Gianfranco Ghirlanda, SJ, distinguished dean of the canon law faculty at

Rome’s influential Gregorian University, is reported to have said recently

“From a canon law perspective, the bishop and the [religious] superior are

neither morally nor judicially responsible for the acts committed by one of

their clergy.” (Assoc. Press, 18 May 2002, article by Tom Rachman).

Perhaps

Professor Ghirlanda was misquoted or his remarks taken out of context.

In any case, the claim that bishops and religious superiors are neither

morally nor judicially responsible for acts of their clergy seems difficult to

reconcile with Canon 128 of the 1983 Code of Canon Law that states: “Whoever unlawfully causes harm to another by a juridical act, or indeed by any other

act

which is deceitful or culpable (actu dolo vel culpa posito), is obliged to repair the damage done. (British

trans.)” The Americans render the operative phrase “with malice or

negligence”. Either way, the canon (one, incidentally, that greatly expands

the scope of ecclesiastical liability for malfeasance in office over its 1917

Code counterpart, Canon 1681) is a clear enunciation of the obligation of

persons in the Church (there being no exemption for bishops in this regard) to

make good harms unlawfully caused as a result of their actions or omissions.

The

pertinent claim is that the some bishops (not all, but at least some) placed

priests known to them to be pederasts or homosexually active in positions

wherein they could and did sexually abuse minors. A man who knows his hound

snaps at children must not allow such an animal to run free through the

neighborhood. If he does so, and if a child is bitten by such a dog, the owner,

I suggest, is morally and juridically liable not for biting children himself,

obviously, but for knowingly allowing a situation to arise wherein children

could predictably be bitten by his dog. The same would seem to apply to bishops

who knowingly assigned to parish ministry priests with a known proclivity to

toward sex with minors.

|

Bp.

Wilton Gregory outlined an approach

to

episcopal responsibility for clerical misconduct cases that was

forthright and balanced. Read his June

13th address. |

If

that analogy limps in some ways (e.g., dogs don’t have free will, but priests

do), consider the case of one man who freely lends his automobile to another

despite knowing that the other is a reckless driver. The owner’s good driving

record is not at issue when the other man causes a tragic accident, but his

prudence in helping to make possible the crash by enabling the reckless man to

have access to a car, is.

Of

course, in these dark days, some wish to impose to a “strict liability”

standard on bishops in all priestly sex abuse cases, holding bishops financially

responsible for harms caused by their priests notwithstanding the bishop’s

lack of knowledge of the danger. This is wrong and unjust. Others, in cases of

some genuine liability on the part of the bishop, wish to exaggerate that

liability out of anger or greed. This is opportunism. Both approaches should be

rejected.

But I

believe it is a mistake to make the blanket claim that there is no canonical

basis for episcopal liability for harms arising from priestly misconduct. There

is a basis for such liability in canon law. Only a fair, case-by-case,

examination of the facts will determine whether such liability is warranted in a

given case, and if so, how much compensation should be awarded. +++

|

Top

|| Home

|| Canon

Law || Liturgy

& Sacraments || Catholic

Issues || Personal

|