|

To work for the proper implementation of canon law is to play an extraordinarily constructive role in continuing the redemptive mission of Christ. Pope John Paul II |

|

30 sep 2022 |

Research links

|

Resources for studying the 1917 Code in English, here.

Pont. Commission for the Codification of Canon Law, here. |

|

Overview

|

Reading Footnotes for the 1917 Code |

|

|

Dr. Ed's solaranite-powered guide to the footnotes of the 1917 Code |

|

The footnotes to the 1917 Code are intimidating but now there's hope! Ed Peters, in the spirit of Ed Wood, presents ...

It is unquestioned that the footnotes to the canons of The Code of Canon Law are of inestimable benefit in the interpretation of law. E. Roelker, The Jurist 7 (1947) at 355.

|

|

|

Not all provisions in the 1917 Code have footnotes. If you need to know which ones don't have footnotes, see Fontes IX: 2-11.

In canons with numbered subdivisions, a footnote for a subdivision applies only to that subdivision. Canons can, and many do, have more than one footnote.

In the 1917 Code, footnote numbering starts over with each page. Because different editions arranged pages differently, footnote numbers often changed from edition to edition.

When multiple citations are made to the same authority (such as, here, Benedict XIV or the Holy Office), that authority is not re-identified each time. You just have to supply it.

|

Wow. Large blocks of finely printed, densely packed, alpha-numeric Latin abbreviations. What could be less inviting? (okay, besides going to the Albuquerque ball with Co-Pilot Danny at 4 a.m.)? Put-off by the seeming impenetrability of Pio-Benedictine footnotes, many researchers give up consulting them without even trying. And that's a pity. The provisions of the Pio-Benedictine Code reflect nearly two millennia of accumulated pastoral and legal wisdom, and their footnotes identify more effectively than can be imagined the almost-countless occasions for refining that wisdom. Let's see how.

The first canon of Book II of the 1917 Code of Canon Law reads as follows:

Can. 87. By baptism a human is constituted a person in the Church of Christ with all of the rights and duties of Christians unless, in what applies to rights, some bar obstructs, impeding the bond of ecclesiastical communion, or there is a censure laid down by the Church.

There is a footnote to this canon, as it happens, one that contains a sample of almost everything one might find in a Pio-Benedictine footnote. We will use this footnote as a model below but for now let's just see what it looks like:

Don't be concerned if almost nothing in this footnote makes sense yet. Almost nothing in Plan Nine from Outer Space makes sense, but that doesn't detract from its greatness. So, after you've let your how-am-I-ever-going-to-do-my-JCL-thesis-if-I-can't-even-read-the-footnotes-to-the-1917-Code anxiety recede, take a deep breath and look more carefully at each line in the note.

Surely you recognized the names of some popes (e.g., Benedict XIV or Pius IX). That tells you something, namely, that papal writings contributed to the formation of Pio-Benedictine law. You probably also recognized several dates (e.g., November 22, 1439, and April 25, 1902). From that you see first that Cdl. Gasparri used the European dating convention (day-month-year) in his citations but, more importantly, you see that documents from many centuries were culled during the drafting of this canon. The 1917 Code was not thrown together by folks with no sense of canonical history. Finally, you might have recognized the names of some locations such as Quebec, Bucharest, or Nanking. Even that is useful: it underscores that the 1917 Code, a law intended to be applied throughout the Catholic world, drew on experiences garnered from around the world.

Not a bad set of observations for someone who thinks he can't figure out what's contained in the footnotes to the 1917 Code. Now, on to bigger things.

|

|

took a short cut.

Gasparri

Some provisions in the 1917 Code have footnotes that refer to the footnotes of other provisions. This was doubtless a time-saving device. It is clear, though, that Gasparri considered "vide etiam" footnotes as footnotes for both the original and the referred provisions.

|

If we color-code those four categories thus:

and highlight them in our Canon 87 footnote, we can see:

C. 31, C. XXIV, q. 1; c. 51, D. I, de poenit.; c. 2, 15, de haereticis, V, 2, in VI°; Conc. Trident., sess. VII, de baptismo, can. 7, 8, 13, 14; sess. XIV, de poenitentia, c. 2; Eugenius IV (in Conc. Florentin.), const. "Exsultate Deo", 22 nov. 1439, § 10; Benedictus XIV, const. "Etsi pastoralis", 26 maii 1742, § VII, n. XI; ep. encycl. "Inter omnigenas", 2 febr. 1744, § 16; ep. "Postremo mense", 28 febr. 1747, n. 52; ep. "Singulari", 9 feb. 1749, § 2, 12-16; Pius IX, litt. ap. "Multiplices inter", 10 iun. 1851; Syllabus errorum, prop. 54; Leo XIII, litt. encycl. "Sapientiae", 10 ian. 1890; S. C. S. Off., instr. (ad Archiep. Quebecen.), 16 sept. 1824, ad 2; 19 apr. 1837; instr. 22 iun. 1859; 7 apr. 1875; (Bucarest), 8 maii 1889; instr. (ad Vic. Ap. Nankin.), 26 aug. 1891; S. C. de Prop. Fide (C. G. - Albaniae), 18 apr. 1757, ad 5; (C. G.), 19 aug. 1776; instr. (ad Praef. Ap. Mission. Epiri), 25 febr. 1837; litt. encycl. (ad Ep. Indiar.), 25 apr. 1902.

See? That's not so bad. Again, don't worry if you can't decipher the citations within each grouping. For now we only want to establish that virtually all Pio-Benedictine footnotes are limited to these four fundamental categories. Moreover, citations to these sources will always be presented in the above order. Thus, with only a little practice, one will be able to tell instantly whether, say, any Corpus Iuris Canonici references are found in a given footnote. Likewise, if one is looking only for, say, Tridentine contributions to legal formulations, there is no need to hunt through an entire, sometimes quite lengthy, footnote to find out whether there are any. You now know exactly where in the footnote to look for such cites.

|

|

Notes:

The four categories of Pio-Benedictine sources can be traced to the consultors' first directions for the codification project when they specified examination of "the Corpus ... the Tridentine Council, the acts of the Roman Pontiffs, and ... decrees of the Sacred Roman Congregations or Ecclesiastical Tribunals..." See Gasparri, Preface, in Peters trans., 17.

|

Examine the footnotes to the following canons and verify whether you can identify the categories and number of references in those categories that are found in each.

3. Using the four fundamental categories of citations

I'm now going to explain in some detail how to use all four categories of Pio-Benedictine footnotes, but the first category, the Corpus Iuris Canonici, is frankly the most difficult. Feel free to skip to Council of Trent (very easy), Papal Writings (easy), or Roman Curia (pretty easy once someone shows you), and save the Corpus citations till your confidence is built up on the other three categories. Or, just dive in. Your call.

|

|

If a title heading is given in a Corpus footnote, it may be disregarded, as the title number is sufficient to identify the source. It's rather like today, if someone cites to "Book III: Teaching Office," one does not need to know that Book III is called "Teaching Office" in order to find it in the Code.

Gratian's first 20 Distinctions (Fontes IX: 14), along with what is called their Ordinary Gloss, are available in English. See: Thompson & Gordley, trans., Gratian: The Treatise on Laws (CUA, 1993). It's a terrific work, laid out exactly as students would have studied it for hundreds of years.

Click here for a list of citations to

The Quinque Libri Decretalium Gregoriani IX are available on-line:

To find out quickly which chapters of Gregory's Decretals were impacted by later legislation contained in the Corpus, irrespective of Gasparri's use of such materials, click on my Ius Decretalium page.

The famous Regulae Iuris are found in two places within the Corpus: a short list is found at the end in Gregory's Decretals and is cited as part of Book V, title 41; the more important list is found in the Liber Sextus. It has a special citation system: "Reg. 1, R.J., in VI°" means "Rule 1 of the Regulae Iuris in the Liber Sextus." My own page on the Regulae Iuris is here.

Documents named in the Fontes tables of contents are necessarily arranged by date, so one could look for dates in them as well.

|

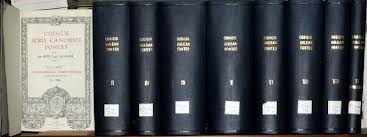

Category 1. Corpus Iuris Canonici. This monumental work was compiled between 1140 and 1500 and actually consists of six smaller works. The six constituent parts of the Corpus Iuris Canonici are:

• Concordantia discordantium canonum (c. 1140)

Gratian's masterpiece is known by various titles: Concordantia discordantium canonum, Decretum Gratiani, Gratian's Decree, all refer to the same work. Cited hundreds of times in Pio-Benedictine footnotes (See Fontes IX: 14-55), Gratian's Decretum is divided into three parts.

Predictably then, "c. 1, D. I, de cons." means "canon 1 of Distinction 1 of Part Three (called de consecratione) of Gratian's Decree."

There are only two (well, maybe three) things that can confuse folks in Gratian citations. First, question 3 of Cause 33 is divided into "Distinctions", which are in turn divided into "canons". It is also not called "Question 3 of Cause 33" but rather, "de poenit." short for "de poenitentia". Thus, "c. 6, D. I., de poenit." means "canon 6 of Distinction I of Question 3 of Cause 33 of Part Two of Gratian's Decree." Second, the Roman numeral letter "X" for number 10 can be confused with a very common abbreviation for the second part of the Corpus Iuris Canonici, the Liber Extra, to which we'll turn immediately below. Third, one might be confused by the fact the letter "c." stands for "canon" in Gratian, but, as we shall see, for "chapter" in the rest of Corpus.

• Quinque Libri Decretalium Gregoriani IX (1234)

The single work, Five Books of the Decretal (Letters) of Pope Gregory IX, was known commonly as the Liber Extra, or the book of things "outside" of Gratian's Decree. It is always identified by the single letter "X" and is cited hundreds of times in the 1917 Code. See Fontes IX: 55-102. The Liber Extra is divided into five "books", all of which are in turn divided into "titles", all of which contain "chapters" (not canons). The illogic of the common citation system is distressing, but here goes: "c. 7, X, I, 2" means "chapter 7 of title 2 in book I of the Liber Extra." Everyone admits the citation system makes little sense. Too bad, really. The vitally important Decretals of Gregory were actually quite well laid out by St. Raymond Peñafort.

• Clementinae (1317)

The Clementinae are the constitutions of Pope Clement V, though their final form was given by Pope John XXII when he promulgated them in a revised state. Abbreviated in Pio-Benedictine footnotes as "in Clem." they, like the Liber Sextus, basically followed the organization of Gregory's Decretals. Thus "c. 2, de electione et electi potestate, I, 3, in Clem." means "chapter 1 of title 3 (called de electione et electi potestate) of Book I of the Clementinae."

• Extravagantes Joannis XXII (1322)

The Extravagantes Joannis XXII arranges decretal letters of John XXII into titles and, under them, chapters (but not books). Thus "c. 2, de electione et electi potestate, tit. I, in Extravag. Ioan. XXII" means "chapter 2 of title 1 (called de electione et electi potestate) of the Extravagantes Joannis XXII.

• Extravagantes communes (1499-1502)

The last part of the Corpus Iuris Canonici gathers other materials deemed useful by the French legal scholars Jean Chappuis and Vitalis de Thebes and organizes them once again under the book-title-chapter format. Thus "c. un., de consuetudine, I, 1, in Extravag. com." means "chapter one [by the way, indicating the only chapter in that group] of title 1 (called de consuetudine) of Book I of the Extravagantes communes.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is how to trace Pio-Benedictine citations to the Corpus Iuris Canonici. Hmmm, maybe that wasn't so tough after all. In any case, compared to the Corpus citations above, the other three categories of footnotes explained below really are much easier to follow.

|

|

There are nine plans from outer space for the take-over of the world.

There are nine volumes in Gasparri's Fontes.

Coincidence?

|

Category 2. Council of Trent. The Nineteenth Ecumenical Council met in 25 sessions from 1545 to 1563. There were some lengthy adjournments during that time, and only half of the sessions produced anything canonically significant, but it is one of the outstanding legislative councils of the Church. Over 250 Tridentine provisions were cited in hundreds of Pio-Benedictine norms. See Fontes IX: 119-135. Reliable editions of the canons and decrees of the Council of Trent were so widely available that Gasparri did not reprint them in his Fontes. Today, moreover, modern language translations of Trent are plentiful. In brief, Pio-Benedictine citations to the Council of Trent are good news for researchers: the council was of great importance in itself, and its provisions are easy to find in both Latin and the vernacular. But note: Trent is not the only ecumenical council cited in the footnotes of the 1917 Code.

Third, some of the writings that Gasparri listed as 'papal' occurred during or in connection with an Ecumenical Council. See, e.g., the citation to Pope Eugenius IV in our sample footnote above. While Gasparri noted the conciliar context for such writings, he treated them as papal for category assignment purposes. There, I told you category two citations were easy. Now, on to category three.

|

|

Plan 9 from Outer Space premiered in 1959.

John XXIII announced the revision of the Pio-Benedictine Code. in 1959.

Coincidence?

|

Category 3. Papal writings. Beginning with St. Clement I and ending with Benedict XV many popes provided resource materials for hundreds of Pio-Benedictine canons. See Fontes IX: 135-170. Of course, certain popes stand out for the number and quality of their contributions, for example, Benedict XIV (not surprisingly) and most of the popes after Vatican I. In any case, the papal writings category is very simple to master so let's explain it now.

Gasparri published, in chronological order, all papal writings that served as sources for Pio-Benedictine law in the first three volumes of his Fontes. There are various ways to find the papal writings cited in 1917 Code footnotes but I'll tell you the best. Even it's a little weird.

Recall that Pio-Benedictine footnotes citing papal writings give the name of the pope, the document title, the date of issue, and perhaps some internal reference numbers. The crucial datum for you, though, is date of issue.

Make your best guess as to when the pope appeared in Church history (early, middle, late), open up Fontes volume 1, 2, or 3, and page through it till you see a bold print document header (it doesn't matter which one it is). The header will always contain a reference number, a papal name, document type and title, and the date of issue. For example, in Fontes II, at p. 434, one finds: 430. Benedictus XIV, const. Pastoralis, 15 jul. 1754.

Remember: many papal writings have been translated into the vernacular. For example, all papal encyclicals from Benedict XIV though the first part of John Paul II's reign appear in English in Claudia Carlen, ed., The Papal Encyclicals (1740-1981), in 5 vols., Pierian Press, 1990.

Finally, when a reference within a papal writing footnote (e.g., a "§", or "n.", etc.) is given, one may skip directly to that part of the document in the Fontes. Else, one needs to look at the entire document to determine its relevance for your research. Click here for the standard Papal-Writing/Roman Curia Warning.

You've only got one category left, and even that is not hard once you've seen how it's put together. Really.

|

|

|

Dicastery name abbreviations can be frustrating so let's start with them. In the order they appear in both the footnotes and the Fontes, they are:

Fontes IV

Fontes V

Fontes VI

Fontes VII

Fontes VIII

Having selected the volume in which the dicastery you need is reported, the "guess-and-hunt method" outlined above for finding papal writings is the most efficient way to track down specific Roman Curia citations, too. As before, when a reference within a Roman Curia footnote (e.g., a "§", or "n.", etc.) is given, one can skip directly to that part of the document in the Fontes. In other cases you'll need to look at the whole document. And don't forget the standard Papal-Writing/Roman Curia Warning.

|

|

The latest, pre-1917 Code versions of liturgical books I found are:

Missale Romanum 1912, 1914

Pontificale Romanum 1888, 1891

Caeremoniale Episcoporum 1853, 1860

Rituale Romanum 1891, 1913

|

That's it! That's all four major categories of citations in the footnotes to the 1917 Code. Let's pull it all together, now, and see whether you can find the fontes to our sample footnote above. Find these sources on your own, and then check with the list below to make sure you are right.

Okay, you can go to work right now if you want. What follows are only a few picky points for perfectionists.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

4. Small points for specialists

Gasparri published 6,464 documents in his Fontes, some of them only a few lines long, others running dozens of pages. He (and Seredi, of course) numbered each of them in the Fontes. For most canonical researchers, however, these document numbers are irrelevant. They are never used in the Code's footnotes and one need not know them in order to find the fontes to a given canon. Document numbers really have only one interesting use: If one's research point of departure is the document itself (instead of, as is typical, a provision of the 1917 Code) one can take the document number to various tables in Fontes IX and identify what other canons, if any, the document contributed to.

Suppose for example, that you were interested in how an instruction from the Holy Office dated 6 August 1897 (Fontes IV: 495-496) had been used in the 1917 Code. (Maybe you were led to that document by a reference in one canon, and you were now wondering what other canons, if any, might have drawn on that document.) Noting the document number, 1190, you would turn to Tabella B in Fontes IX and, at col. 183, learn that document no. 1190 had been referenced in the footnotes to: 1917 CIC 904; 1139 § 1; 1940; 1941 § 1, 2; 1942 § 1, 2; and 1944 § 1, 2. Pretty handy, if you ever need to know it. Not very handy if you don't.

Standard Papal-Writing/Roman Curia Warning

At nearly the end of his Preface to the Pio-Benedictine Code, Gasparri writes that "Notes have been added to the canons at the bottom of each page that indicate the various sources from which they were taken..." So far so good; we all knew that. But then Gasparri says "...it is scarcely necessary to add that the canons are not always consistent with all their sources in the parts used..." There's more here than meets the eye.

Many times one will consult a source document for a given canon and at the end of the process frankly wonder what the relevance of that document was to the canon. Sometimes the connection between a document and the norm it allegedly influenced is simply invisible to modern eyes. Whether this is because we contemporaries have lost contact with the environment in which the law grew up and so we do not recognize connections that our predecessors would have taken for granted, or whether the disconnect arises from a decision by Gasparri to err on the side of over-inclusion in his footnotes and fontes, even if that meant including some basically irrelevant materials in some places, I cannot tell. But the problem is there. If you find yourself facing it one day at least know that you are not alone.

|

|

Cdl. Seredi carried on Gasparri's work after his death.

|

5. Resources needed to make use of Pio-Benedictine footnotes

|

|

A final thought...

|

|

|

|

maii 1742, § VII, n. XI; ep. encycl. "Inter omnigenas", 2 febr. 1744,

§ 16; ep. "Postremo mense", 28 febr. 1747, n. 52; ep. "Singulari",

9 feb. 1749, § 2, 12-16; Pius IX, litt. ap. "Multiplices inter", 10 iun.

1851; Syllabus errorum, prop. 54; Leo XIII, litt. encycl. "Sapientiae",

10 ian. 1890; S. C. S. Off., instr. (ad Archiep. Quebecen.), 16 sept. 1824, ad

2; 19 apr. 1837; instr. 22 iun. 1859; 7 apr. 1875; (Bucarest), 8 maii 1889;

instr. (ad Vic. Ap. Nankin.), 26 aug. 1891; S. C. de Prop. Fide (C. G. -

Albaniae), 18 apr. 1757, ad 5; (C. G.), 19 aug. 1776; instr. (ad Praef. Ap.

Mission. Epiri), 25 febr. 1837; litt. encycl. (ad Ep. Indiar.), 25 apr. 1902.

maii 1742, § VII, n. XI; ep. encycl. "Inter omnigenas", 2 febr. 1744,

§ 16; ep. "Postremo mense", 28 febr. 1747, n. 52; ep. "Singulari",

9 feb. 1749, § 2, 12-16; Pius IX, litt. ap. "Multiplices inter", 10 iun.

1851; Syllabus errorum, prop. 54; Leo XIII, litt. encycl. "Sapientiae",

10 ian. 1890; S. C. S. Off., instr. (ad Archiep. Quebecen.), 16 sept. 1824, ad

2; 19 apr. 1837; instr. 22 iun. 1859; 7 apr. 1875; (Bucarest), 8 maii 1889;

instr. (ad Vic. Ap. Nankin.), 26 aug. 1891; S. C. de Prop. Fide (C. G. -

Albaniae), 18 apr. 1757, ad 5; (C. G.), 19 aug. 1776; instr. (ad Praef. Ap.

Mission. Epiri), 25 febr. 1837; litt. encycl. (ad Ep. Indiar.), 25 apr. 1902.